Susan Tassin was hiking with her husband one day along a Pennsylvania trail when they came across stacked cut stones in a large rectangle. Tassin recognized what she was seeing as the foundation of a house. The home was long gone, and the stones were all that remained to mark that someone had once called that out-of-the-way place home.

Susan Tassin was hiking with her husband one day along a Pennsylvania trail when they came across stacked cut stones in a large rectangle. Tassin recognized what she was seeing as the foundation of a house. The home was long gone, and the stones were all that remained to mark that someone had once called that out-of-the-way place home.

“I was excited,” Tassin said. “We saw some other hikers and told them what we had found.”

The other hikers didn’t understand the Tassins’ excitement. The hikers pointed out a historical marker that told readers the site had once been more than a place for a single home. An entire home had been located there.

It was all gone, though.

All that was left was a ghost town.

When most people think of ghost towns, they picture dusty streets flanked by false-fronted buildings and tumbleweeds rolling down the streets. Yet, some people say that Pennsylvania has more ghost towns than any other state and most of them are in western Pennsylvania.

“Some of the best ones are out here,” Tassin said.

She should know. She has been fascinated by ghost towns since that first discovery on the trail years ago. She has visited many of them and written a book called Pennsylvania Ghost Towns: Uncovering the Hidden Past (Stackpole Books, 2007).

Ghost (town) stories

Ghost (town) stories

Despite being nearly forgotten nowadays, many of these towns have interesting stories to tell.

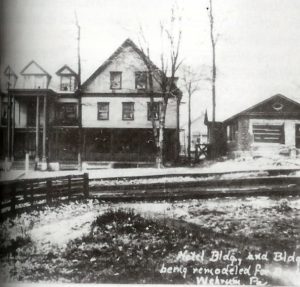

Wehrum in Indiana County was founded in 1901. It was the home for Lackawanna Coal and Coke Factory miners. At its peak, Wehrum had 250 houses, two churches, a school, a post office, a hotel, a bank, and a company story.

In 1909, a gas explosion in Mine #4 killed 21 miners and injured 12 more. This was roughly about 10 percent of the population. Thus, began the town’s slow decline until in 1934, all that remained of the town was a house, the jail, the school, and the Russian Orthodox Cemetery.

Like Wehrum, many of Western Pennsylvania’s ghost towns were former company towns for coal mining operations. Because coal mines were generally not found near a city, coal companies had to build towns where their employees could live and be close to their jobs.

“When the coal mines went away, so did the towns,” said Delores Columbus, executive director with the Cambria County Conservation and Recreation Authority. She pointed out that when the mine closed in Wehrum, the coal company tore the houses down and used the wood to help build buildings in another coal town.

Hassin added that even if the company didn’t tear down the abandoned buildings, other people might.

“In Whiskey Run, there’s not much there, but if you know what to look for, you can see the wood from the houses in their neighbors’ barns and sheds.”

Whiskey Run in Indiana County is one of the ghost towns with a very colorful history. There are at least three versions of how the town got its name from settlers murdering drunken Indians to a post office that sold untaxed alcohol to bootleggers using the water in the creek for their illegal whiskey.

Whatever the origin for the name, the town quickly developed a reputation as being rough and lawless. Duels and gunfights were not uncommon.

In one story, the Bartino family rented rooms to miners. It seems that many of them were smitten by one of the Bartino’s daughters, Maria.

“Three of the men began arguing one afternoon about who should have the right to court the young lady,” Hassin wrote in her book. “The fight, not surprisingly, escalated into physical violence, with the three men rolling around, punching, kicking, and shouting. Into the mix came a fourth suitor, who arrived with flowers in hand, hoping to see Miss Bartino.”

Then, as might be expected in Whiskey Run, guns were drawn and fired. Three of the miners died on the scene. The fourth was injured and died later from his injuries. Even Bartino was injured in the gunplay.

Not all ghost towns are related to the coal industry though. Some towns wound up being buried under a man-made lake. This is what happened to Aitch, which is now under Raytown Lake.

Other towns met a different fate.

“Hannah’s Town doesn’t exist anymore because the Indians burned it down,” said Anita Zanke, the library coordinator with the Westmoreland County Historical Society.

The town was the first county seat for Westmoreland County in the late 18th century. The Indians and British soldiers burned the town in 1782. It is now rebuilt as a historical site.

Still other towns might still exist, but it as a shadow of its former glory.

“It’s hard to have a town called a ghost town when people still live there, but they are much smaller towns,” Hassin said.

Iselin is such a place. Founded as a coal town in 1902, Iselin grew quickly to more than 1,000 residents. Housing construction couldn’t keep up with the demand. However, as the demand for coal disappeared so did the population. The mines closed in 1935.

Iselin still exists today as a suburban community where you can still see signs of the former coal town in the architecture of some of the older buildings.

The Ghost Town Trail

Cambria and Indiana counties decided to turn interest in ghost towns into a tourist attraction. The two counties developed a 36-mile-long trail along the old railroad line that passes near 10 ghost towns from Saylor Park in Indiana County to Ebensburg in Cambria County.

The trail was first opened in 1994 and gets about 75,000 hikers and bikers annually, according to Columbus.

“This is our 20th year since we first opened in October 1994,” Columbus said.

For more information on the trail, visit www.indianacountyparks.org/trails/gtt/gtt.html.