At first, parents thought their children had been playing too hard. They developed fevers and some of them got headaches. The symptoms would pass, though, but then a few days later, the children would get stiff necks or backs. Some would experience constipation. If they were lucky, that is all that would happen.

At first, parents thought their children had been playing too hard. They developed fevers and some of them got headaches. The symptoms would pass, though, but then a few days later, the children would get stiff necks or backs. Some would experience constipation. If they were lucky, that is all that would happen.

Unfortunately, not all the children were lucky. Some of them would be playing and fall over unable to use their legs or arms. Others would wake up in the morning unable to move. A few even died unable to breathe.

The disease was called infant paralysis in 1918, though it is now better known as polio. The epidemic in Franklin County began in Waynesboro in June 1918 and continued through the fall. Forty-six cases were reported in the county with six children dying because of the disease. Chambersburg had 15 of those case and two deaths.

Though polio has been around for centuries, major epidemics weren’t seen until the early 20th Century when they appeared in Europe and the United States.

Polio damages the nerve cells, which affects a person’s muscle control. Without nerve stimulation, the muscles weaken and atrophy. This can lead to paralysis and if the muscles that help the body breathe are affected, the paralysis can cause death because a patient is unable to breathe.

Two years prior to the Franklin County epidemic, there had been over 27,000 cases of polio in the United States resulting in more than 6,000 deaths.

The first line of defense in fighting polio was to quarantine homes where there were outbreaks of polio and the families had to place placards in their windows as a notice of the quarantine.

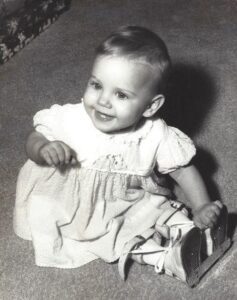

Sometimes it would go further. An infant girl of the H. H. Harrison family in Guilford Township was stricken with polio in September 1918. Though she was not in serious condition, “She has eight brothers and sisters all at home and all attending school in Guilford. The school will be ordered closed today by Health Officer Kinter. The home will be will be quarantined today,” the Public Opinion reported.

Sanitary and hygiene campaigns were undertaken to encourage people to drink and bathe in clean water. Better hygiene meant that not only was it less likely a child, or even an adult would develop polio, but also more likely that the symptoms would be mild. However, this also meant that it was more likely that older children would develop polio and it would be the harsher, paralyzing form.

Little more could be done because doctors of the time were uncertain just what polio was and it was decades before a vaccine would be developed.

A 1916 article in the New York Times outlined the problem that doctors faced, noting “fighting infantile paralysis consists largely in doing everything that seems effective in the hope that some of the measures taken will be effective.”

Tony Gould wrote in A Summer Plague: Polio and Its Survivors about some of the treatments used at the time to unsuccessfully cure polio. Doctors would “Give oxygen through the lower extremities, by positive electricity. Frequent baths using almond meal, or oxidising the water. Applications of poultices of Roman chamomile, slippery elm, arnica, mustard, cantharis, amygdalae dulcis oil, and of special merit, spikenard oil and Xanthoxolinum. Internally use caffeine, Fl. Kola, dry muriate of quinine, elixir of cinchone, radium water, chloride of gold, liquor calcis and wine of pepsin.”

Unfortunately for Franklin County, residents had just begun to breathe a sigh of relief from the infantile paralysis epidemic to deal with an even greater threat called the Spanish Flu.

You might also enjoy these posts:

- Patrick Gass: Explorer, Soldier, Patriot from Franklin County

- Right city, wrong state

- Small-town high school students prepare for the journey of a lifetime in the middle of the Great Depression (Part 1)