Spanish Flu first appeared in Adams County around the end of September 1918. It almost always it made its first appearance in any community during the last week of September, whether it was here or in Europe where there was fighting. This could indicate that that there wasn’t a flash point location so much as this was the strain that had developed in 1918 and mutated. That is a point that is argued, though. Some have tried to set an origin point. Boston and in Kansas are the most-common locations suggested.

Spanish Flu first appeared in Adams County around the end of September 1918. It almost always it made its first appearance in any community during the last week of September, whether it was here or in Europe where there was fighting. This could indicate that that there wasn’t a flash point location so much as this was the strain that had developed in 1918 and mutated. That is a point that is argued, though. Some have tried to set an origin point. Boston and in Kansas are the most-common locations suggested.

The Gettysburg Compiler reported on Sept. 28 that the flu had broken out in Camp Colt, Gettysburg’s army training camp. At this point, they believed that it had come from soldiers who had been exposed to it in Camp Devens in Massachusetts, which is one of the places in an area where the flu was believed to have started.

To combat it at Camp Colt, 500 soldiers were getting daily throat sprays, which were believed enough to stop the flu. The newspaper reported, “The epidemic seems to be well in hand with treatment before the severe stages.” However, within this first week of breaking out, 125 men had been hospitalized and five had died. These were the men who had come from Camp Devens.

Another factor that may have played into the spread of the flu and how deadly it was that the U.S. was sending soldiers into military camps all across the country. These camps were by and large tent camps, which I’m sure weren’t conducive to staying healthy in the winter. They were also overcrowded in many cases.

Is it any wonder that the flu found fertile ground in a military camp? I think this also partially explains the W-shaped death curve of the flu. Generally, when flu is fatal, it is with the youngest and oldest in the population, those whose immune systems were weakest. Spanish Flu also spiked in the middle with 20-30 year olds roughly. This would be the age range for soldiers, particularly those who were living in tighter quarters and unhealthier conditions than they might have been ordinarily.

During the first week of the outbreak, no mention was made of the problem in the local papers. Out of sight, out of mind. Yet, the problem was growing.

It had already reached epidemic status in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia by Oct. 4. Also, by the middle of October, the state reported that there had been 6,081 deaths from the flu and 2,651 deaths from pneumonia, which was a complication of the flu. Also, the thing to remember and was widely reported all over the world is that doctors were so overwhelmed that many deaths didn’t get reported.

The Compiler ran this headline in early October, which seemingly came out of nowhere since the paper hadn’t been reporting on the buildup to it: “The Answer to the Scourge is a Demonstration by Community to Flight It to the Limit. Never has Gettysburg been so stirred as by the scourge of Influenza. Never has the heart of the town been so wrung as by the scourge carrying off the soldier boys who as answered their country’s call in defense of her principles.”

Father W.F. Boyle offered Xavier Hall as a hospital. Sixty-four cots were set up in the hall as it was transformed into an emergency hospital. Prof. Lamond, who was director of the Red Cross locally, sent for nurses to care for the sick and the Soldier’s Club House on Middle Street was converted into the temporary living quarters for the nurses. In a show of community spirit, Mrs. Burton Alleman of Littlestown had schoolchildren canvass the town for donations for the hospital. They raised $100 and collected 59 water bottles, 10 fountain syringes, 15 ice caps, 500 sputum cups and 25 serving trays.

Father Boyle believed that it would be easier to control the flu if you could isolate the sick from the healthy. It was a good idea, but it was too late.

Two days after the hospital opened, the county schools were closed, which was a common defense against the flu. It was also announced that in less than two weeks, there were 92 dead at Camp Colt.

By Oct. 12, about three weeks after flu broke out, the Compiler, which had just a few days before proclaimed the flu abating, now said that it was the “most heartrending epidemic the town has ever been through. … Distress has pervaded the hearts of our people but around this dark cloud is the glow of the wonderful demonstration of our people in town and country and nearby places.”

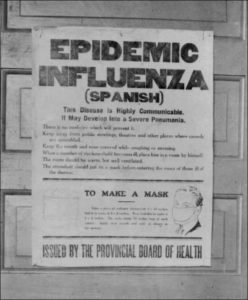

Around this time is when people start getting worried. Body counts scare them, especially when there’s little they could do about it. Warnings were issued and sick families were quarantined. Some people even took to wearing masks, just like they did when they feared SARS.

Camp Colt now had 100 dead soldiers. This was one out every six soldiers at the camp and many of the 500 remaining were sick with the flu.

The newspaper also said that Father Boyle’s act helped control deaths. Not really. His goal had been to contain the sickness, but several of the nurses caring for the soldiers contracted the flu and wound up becoming patients themselves. One of the nurse aides also died from the flu. Even Professor Lamond caught the flu.

This is one of the insidious ways that the Spanish Flu worked. Many communities were already shorthanded medically because doctors had been drafted to serve in WWI. Then along came the flu, which intensified by the shortage by making many of the remaining doctors sick at a time when the workload was drastically increasing. The remaining doctors found themselves working longer hours with contagious people. This would wear them down and make them susceptible to flu and the process would repeat.

By this time, the bodies were beginning to pile up, literally. The dead soldiers were taken to the Grand Army of the Republic Hall in town until arrangements could be made to ship their bodies home. As each body was taken to the depot, it was given a military escort. This must have been a depressing sight for residents to see 100 times as each soldier was taken to the train that would return him home.

Half of the front page was being taken up with obituaries of people who died from the flu.

In one instance, George Pretz was the author of the lyrics for the Gettysburg College fight song. He was an army doctor who died in Syracuse. When his wife, Carrie, heard he was sick, she started up to New York, but she didn’t arrive until after he had died. His brother-in-law, Edgar Tawney, “went to Hanover on Monday for flowers and while sitting in an automobile was stricken and being brought home died early Tuesday morning.”

By mid-October, all pretense of optimism was gone. The Gettysburg Times had an article with the ominous headline, “Death’s Harvest Still Continues.”

But then a week later, the reports were suddenly upbeat. The Times declared that the flu was all but gone from Camp Colt.

As side story that began to percolate was that Health Officer F.Y. Stambaugh in Hanover was accused of negligence in caring for the sick. He was accused of failing to look after quarantined families and fumigate houses marked for flu.

A similar story to this one is that George Stravig son, brother and sister all died within a week of each other because of the flu.

Through November, there truly was a lessening of the flu cases. People started to breathe a sigh of relief. Then Adams County then suffered what only a few places around the country saw, a second spike in the flu.

Also, by the end of October, the Times was reporting that 23,000 Pennsylvanians had died from the flu. That represents roughly ¼ of 1 percent of the state’s population that died in October and the month still had five days left in it when this was reported.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that the flu peaked in Philadelphia during the week of Oct. 16. On that day, not that week, that day, 700 Philadelphians died. Pittsburgh saw its peak three weeks later. So Adams County most likely saw its peaks somewhere in between.

The emergency hospital at Xavier Hall quarantine was lifted at the end of the month and by this point 148 people who had been sent there had died.

By the end of October, there was a sense of confusion about the flu. The way it was striking across the county was inconsistent. The Halloween parade in town was cancelled, but the bans about public gatherings were slowly being lifted.

Yet, the tragedies continued.

You might also enjoy these posts: