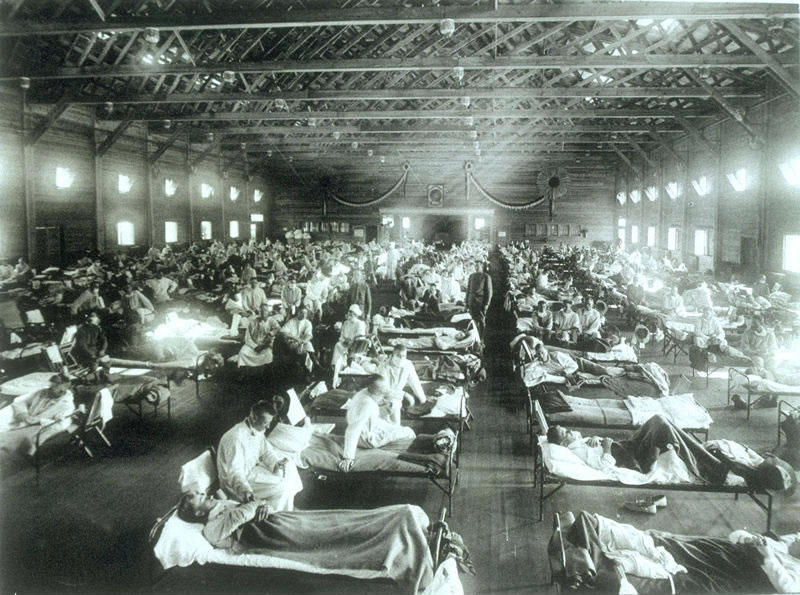

A Spanish Flu emergency hospital in Kansas.

Elmer Martin, who lived near Crellin, returned to work on October 15, 1918, after being sick for a few days. The 28-year-old felt fine and needed to get back to earning a living at the Turner-Douglas Mine as a driver.

He seemed fine his first day back, but when he didn’t report to work the next day, someone realized that he had never made it home. A search began and lasted all night until Martin’s body was discovered alongside the tracks of the Preston Railroad.

He had apparently just fallen down and died.

He wasn’t the only one, either. Across Garrett County, more than 100 people died from Spanish Flu in fall of 1918. The flu wasn’t just a problem in the county, either. Spanish Flu reached nearly every place on the globe and by the time it subsided at the end of November, an estimated 50 million people had died from it.

One physician wrote that patients rapidly “develop the most vicious type of pneumonia that has ever been seen” and later when cyanosis appeared in patients “it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate.” Another doctor said that the influenza patients “died struggling to clear their airways of a blood-tinged froth that sometimes gushed from their mouth and nose.”

The flu seemed to sneak up of Garrett County officials. At first, the many illnesses and deaths were written off as the result of a typical flu outbreak. Many areas in the country began seeing the effects of the flu in late September. In Garrett County, an increase in the number of deaths could be seen, but there was no mention of a problem with Spanish Flu.

Then on October 8, U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue sent a telegram to county officials ordering all public meetings, public places of amusement, and schools to be closed. “The order is drastic and was promulgated for the purpose of conserving the public health. Its effect will be to close all churches, Sunday schools and all manner of gatherings,” the Republican reported.

These restrictions were actually mild compared to some areas. Washington, D.C., San Francisco and San Diego passed laws forcing their citizens to wear gauze masks when outdoors. Some towns required a signed certificate of health if someone wanted to enter the town.

The flu caused a domino effect in various professions. Many doctors had been drafted to fight in World War I, which was winding down at the time. So there was already a shortage of doctors when the increase in flu patients added to their work load. They were exposed to the sick more frequently and many of the remaining doctors took sick themselves. This further increased the workload on the healthy doctors and increasing their chances of exposure to the flu. This happened in Accident, where the town’s sole doctor, Robert Ravenscroft, fell ill with the flu.

Similar things happened with nurses and gravediggers as well.

An article in the Journal of the Alleghenies read, “Bodies of Frostburg servicemen stationed at Fort Meade were sent back to Frostburg wrapped in blankets and tagged. Their bodies were stored temporarily in the corner house where the Frostburg Legion building now stands. Behind the post office in a carriage house, open doors revealed bodies laid on the floor. At the Durst Funeral Home from October 5 to October 31, 1919, ninety-nine bodies were prepared for the last rites. Those bodies, placed in rough caskets or wooden boxes, were carted to the cemetery and stacked until burial.”

Among those people who were buried, the Republican noted that by the middle of the month all funerals were required to be private.

For the next couple weeks, the obituaries of people who died from Spanish Flu took up two columns or more in the Republican. The Oct. 17 headline read “Death List Is Most Appalling Many Fall Victims of the Plague Sweeping the Country”.

In Allegany County, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had 6,000 employees in the county and 1,000 reported sick with the flu on October 4. At its peak, 60 percent of the B&O workers were out sick with the flu.

After one month in Philadelphia, the flu had killed nearly 11,000 people, including almost 800 people on October 10, 1918.

Every business suffered. Coal production fell off because so many miners were sick. Even getting a telephone call through was harder because operators were out sick.

Neither the county or state health departments have precise numbers on how many people died from the flu because cause of death did not have to be reported. The estimate would be between 100 and 150 people died in Garrett County among a population of less than 20,000.

The Spanish Flu is one of the reasons health departments across the country began collecting that type of information. However, even if that information had been collected, overworked doctors didn’t always fill out death certificates for their patients because too many patients who were still living needed their attention.

Spanish Flu killed more people than were killed in World War I and in a shorter time frame, too, yet the war captured the headlines during 1918. Estimates are 675,000 Americans died from the Spanish Flu or ten times more than died in the war.

Spanish Flu killed more people in one year than the Black Plague did in four years.

Spanish Flu was so devastating that human life span was reduced by ten years in 1918.

By the time the flu began to subside in Garrett County at the end of the October, the newspaper notes that it had “visited nearly every abode in Garrett county, leaving death and desolation in its wake.” At this time, Oakland’s new cases and deaths were on the decline while the small Potomac Valley town had yet to reach their peak, though the growth in new cases was slowing. Also, the Republican notes that although everywhere in the county was hit with cases of the flu, “Some sections of the county have been particularly fortunate in not have a case of influenza with its resultant fatal termination. Especially is this true of Accident, Bittinger and the town of Grantsville.”

Spanish Flu is the deadliest plague that has ever struck the world and yet, it remains largely forgotten either through the selective memories of the people who lived through it or because history books remember World War I and not the flu.

Whatever the reason, October 1918 remains the month that the world mourned.

You might also enjoy these posts: