On the day that construction began on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on July 4, 1828, the pressure was on the work crews to get dig the 184.5-mile-long ditch to Cumberland as quickly as possible.

On the day that construction began on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on July 4, 1828, the pressure was on the work crews to get dig the 184.5-mile-long ditch to Cumberland as quickly as possible.

Why the rush? The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad broke ground in Baltimore for its construction began on the same day and Cumberland was the prize for both the canal and railroad.

The C&O Canal crews worked hard digging the canal and building 160 culverts, 74 lift locks, and 11 aqueducts. However, the canal has only one tunnel—the Paw Paw Tunnel—and it was a major reason why the B&O Railroad beat the C&O Canal to Cumberland by eight years.

Construction

When planning out the route of the C&O Canal, it could have continued to follow the Potomac River through southeastern Allegany County, weaving along the Paw Paw Bends or cut through a mountain. Following the bends in the river would have been the easier course, but cutting a tunnel through the mountain would save five miles and could be done in two years, according to the engineering estimates.

The contractor chosen to dig the tunnel was a former Methodist minister named Lee Montgomery. He began hiring men to work on the tunnel in June 1836. The crews worked from either end of the tunnel digging into the mountain and from above cutting down into the mountain.

Four shafts were dug into the mountain to work from above the mountain. They were set in pairs; one shaft of each pair allowed for debris removal and the other was for ventilation. The northernmost pair of shafts was 122 feet deep and the southernmost pair of shafts was 188 feet deep.

The crews initially blasted away large areas of rock with black powder and then shaped the tunnel with picks and shovels. Workers hauled the rubble out of the tunnel using horse carts.

“The workers were not experts at blasting, and there was a great deal of overbreakage; the excavation was 40 percent larger than needed,” Elizabeth Kytle wrote in Home on the Canal.

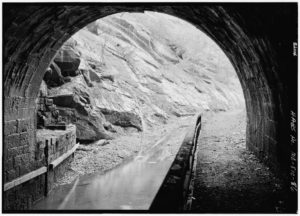

Once excavated, the tunnel arch was formed from layer upon layer of bricks. According to Kytle, the Paw Paw Tunnel lining is 13 layers of brick deep with some places having up to 33 layers. Any open spaces remaining above the arch were backfilled with the excavated material.

“The slaty rock was reasonably hard, but loose enough to make frequent trouble by caving in. It was dangerous work and it went at a snail’s pace,” Kytle wrote.

Montgomery had projected before construction began that his crews would be able to bore out seven to eight feet a day. The reality turned out to be that his crews working three shifts each day only managed 10 to 12 feet a week.

Because of the C&O Canal Company’s financial problems, work was suspended on the tunnel from 1842 to 1847 and construction didn’t restart until November 1848. It was completed by a different contractor, McCulloh and Day, and opened for navigation on October 10, 1850.

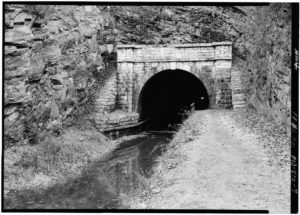

The final 3,118-foot-long tunnel is called “the greatest single engineering achievement on the canal,” by the National Park Service. It is 22 feet wide and 24 feet wide and sheathed in more than 11 million bricks.

Operation

Though the Paw Paw tunnel was an engineering marvel, it was narrow for purposes of the canal. While the canal was designed so that boats could pass each other going in opposite directions, the towpath and canal bed through the Paw Paw Tunnel were both only wide enough for one set of canal mules and one canal boat to move through the tunnel.

Though the Paw Paw tunnel was an engineering marvel, it was narrow for purposes of the canal. While the canal was designed so that boats could pass each other going in opposite directions, the towpath and canal bed through the Paw Paw Tunnel were both only wide enough for one set of canal mules and one canal boat to move through the tunnel.

Because of the length of the tunnel, a canaller upon reaching one entrance of the tunnel could tell if another boat was already in the tunnel, but it was impossible to tell if the boat was approaching or heading away. The canallers started lighting colored lanterns fore and aft on their boats to distinguish direction. A green lantern was hung fore and a red lantern was hung aft. That way, other canallers could tell whether boats in the tunnel were coming or going.

If the boat was showing a green light, the canal boat captain knew that the boat was approaching and pulled over to wait.

Not that problems still didn’t arise.

Some canal boat captains who were in a rush or just plain cranky, refused to yield the right of way to boats in the tunnel. George Hooper Wolfe tells one of the stories in his book I Drove Mules on the C&O Canal.

Two captains—Jim McAlvey and Cletus Zimmerman—and their boats met in the middle of the tunnel. Neither man wanted to back up, and the captains got into a fist fight over who had the right of way. Then things escalated.

“A gun was drawn and would have been used but for the quick action of a mule driver who knocked the gun from the captain’s hand into the Canal,” Wolfe wrote.

Other boats began entering the canal from both ends of the tunnel and soon the tunnel was filled with boats. As day gave way to evening, crew members of each boat began starting corn cob fires in their cabin stoves to cook meals. Before too long, the tunnel began filling with smoke from the stoves and making staying in the tunnel very uncomfortable.

This sped up negotiation and the captains reached an agreement so that the boats could start moving again.

When traffic on the canal reached its peak during the 1870’s, a watchman was hired to help regulate the traffic at the Paw Paw Tunnel and keep it from becoming a bottleneck. The watchman enforced the Canal Company rules for using the tunnel and could fine canal boat captains $10 for violating them.

The Tunnel Today

After decades of struggling to be successful, the C&O Canal closed for good in 1924. The federal government eventually bought it $2 million, originally planning to turn it into a parkway. However, public sentiment changed the government’s intention and the C&O Canal became a national park instead.

Even today, the Paw Paw Tunnel is still an impressive structure on the C&O Canal and it is still isolated. While there is a parking area just off Route 51 between Paw Paw, W.Va., and Oldtown, visitors still have to walk about half a mile along the towpath to reach the tunnel.

A flashlight is recommended if you want to walk through the tunnel since it is quite dark and there is no interior lighting. It will also allow you to see some of the features of the tunnel, including the weep hole (openings in the brick liner that allow water to pass through), the rope burns on the wooden railing and the brass plates the serve as 100-foot markers inside the tunnel.

Visitors can also hike a steep two-mile long, Tunnel Hill Trail, over the mountain. This trail passes by where the canal builders lived while the tunnel was being built.

You might also enjoy these posts:

- Secrets of the C&O Canal

- The C&O Canal during the Civil War

- C&O Canal murder mystery has surprising solution