More than 8,700 Confederate Army veterans lived to attend the 50th anniversary reunion of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1913. They camped on the field where General George Pickett and his men had made their brave charge more than mile across an open field into the cannons on the Union Army in July 1863.

More than 8,700 Confederate Army veterans lived to attend the 50th anniversary reunion of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1913. They camped on the field where General George Pickett and his men had made their brave charge more than mile across an open field into the cannons on the Union Army in July 1863.

Veterans of that charge would have been among the old men attending the reunion. They would have looked at the field covered with tents where the veterans camped during the reunion and remembered that the ground had been covered with bodies 50 years earlier. In that desperate charge, many of the unprotected soldiers had been felled by bullets.

Had the veterans returned five years later, they still would have seen tents on the field where so much Confederate blood had been shed. They would have also seen something that would have given them pause, for had Pickett’s men had it in 1863 rumbling across that open field as it was in 1918, Pickett’s Charge would have succeeded.

Tanks in War

Though the idea of a tank had been around since Leonardo da Vinci conceived of an armored wagon, the idea of using a tank in war didn’t come about until 1903, and then, it still took until 1915 to develop a practical model. With the start of World War I and the United States’ entry into the conflict, the U.S. Army began to look for a way to integrate tanks into the service.

The Camp with No Name

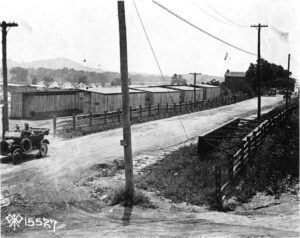

An unnamed U.S. Army camp was first established on the Gettysburg battlefield in May 1917. The reason it had no name, according to the 1918 Report of the National Military Park Commission, was because “we believe it is the practice when the location is at a conspicuous place on United States land, notably battle fields, such as Gettysburg.” The initial location was part of the Codori farm and land where the Round Top branch of the Gettysburg and Harrisburg Railroad was located. The railroad was one of the reasons the army chose the location. It made it easy to move men and equipment directly into and out of the camp.

The camp soon grew as more and more soldiers and supplies were shipped to the camp. Each regiment had 15 or 16 wooden barracks that needed to be constructed. These were not insulated barracks or even fully completed. This temporariness of the construction showed that the camp would not be suitable as a winter quarters for men.

Even though the land where General Pickett had charged would soon be trampled by soldiers once again, the U.S. Army was not ignorant of the historical significance of the park land. In a letter to the Gettysburg Battlefield Commission, the commander of the 61st U.S. Infantry wrote, “…every effort will be made by myself to see that the enlisted men of the 61st infantry do not molest in any way, the monuments, trees, shrubbery, woods, etc. of the Gettysburg National Park.’”

As the soldiers were shipped into the camp, three regiments of infantry were housed on the east side of Emmitsburg Road and one regiment was on the west side. An additional regiment was housed on the west side of the road along with a bakery, hospital and motor ambulance pool. Two more regiments were housed near where the Gettysburg Recreation Park is located.

Water and sewer lines were constructed to deal with the sanitary issues thousands of men would cause. The number of men at the camp grew to 8,000 at its peak, which was roughly the same population as Gettysburg at the time. The men trained through the summer, but by the end of November only a small detachment of men remained because the camp was not suitable to house soldiers through the cold Pennsylvania winters.

Camp Colt

Camp Colt

The army camp didn’t stay deserted for too long. It was re-established on March 6, 1918, with Capt. Dwight Eisenhower commanding. However, this wasn’t going to be the same camp that had been run in 1917. It was going to be a training site for America’s newest weapon, the tank.

“The Tank Corps was new. There were no precedents except in basic training and I was the only officer in the command. Now I really began to learn about responsibility,” Eisenhower wrote in At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends.

Running the camp was Eisenhower’s first independent command. He was given the job of training soldiers to run a piece of equipment that hadn’t been tested in battle yet and to make matters worse, he had to conduct this training without any tanks.

The new camp was named for Samuel Colt, the inventor of the Colt Peacemaker, and the camp was called Camp Colt. Equipment for tank training was moved from Camp Meade in Maryland to Gettysburg where Camp Colt occupied 176 acres of the Codori farm, 10 acres of the Smith farm and 6 acres of Bryan House place. Much of the current Colt Park housing development was also part of the camp.

The training program Eisenhower developed had soldiers practicing with machine guns mounted on flatbed trucks instead of tanks. They learned to repair engines and to use Morse Code. “At times, HQ entertained English officers who had early war experience with the first English constructed tanks on French battle fields. They came to advise on training. Then again, a few members of Congress would arrive to get a peep at the one and only tin can of a tank which was used for partial training of tankers, especially those small men, who could easily climb into its interior. A 200-pound man just couldn’t,” recalled George Goshaw in a 1954 Gettysburg Times article. He had served at the camp under Eisenhower.

Each time a call for tankers to join the fighting in Europe came, battalions of men were moved to Hoboken, New Jersey, where they boarded transports to Europe. There, they joined the fighting climbing inside of real tanks and facing real bullets and mortars.

The camp did manage to get two Renault tanks to use by the time that summer arrived. Over the nine months the camp existed more than 9,000 men were trained to fight in the war.

By October, many of the men had been transferred elsewhere because there were no suitable winter quarters. However, worse than winter happened in the fall of 1918. Spanish Flu swept across the world killing an estimated 50 million people, including 160 at Camp Colt, according to the Gettysburg Star and Sentinel. At one point during the month, the bodies literally began to pile up. The dead soldiers were taken to the Grand Army of the Republic Hall in town until arrangements could be made to ship their bodies home. As each body was taken to the depot, it was given a military escort through Gettysburg.

Closing the Camp

As the flu abated, so did the war. The armistice ending World War I was signed on November 11, 1918. “When November 11th came upon us, Ike and his entire staff were saddened, knowing full well that they were cheated out of actual battle service,” Goshaw recalled. “From then on, there was a let down on training and the necessary daily duties.”

The orders to close Camp Colt came on November 17. Then remaining men were sent to Camp Dix in New Jersey for their final discharge.

Veterans of the camp soon began organizing reunions in Gettysburg, although there was no longer a camp to visit. The first reunion in the 1940’s was marked with the planting of the large pine tree on the east side of Emmitsburg Road south of the entrance to the old visitor’s center. The tree was planted in remembrance of the tankers’ fallen comrades. You can still see it today along with a commemorative plaque summarizing the history of Camp Colt.

You might also like:

- German POWs worked in Gettysburg during WWII

- Gettysburg Home Hosted President Night Before Historic Address

- Find out how the Marines would have fought the Battle of Gettysburg