During his last years of teaching at Philip’s Delight one-room school in Frederick County, Md., William McGill’s day began at 7 a.m. when he would get in the station wagon and drive up Catoctin Mountain on roads “so winding and narrow that he blows his horn constantly to warn the lumber wagons which frequently come the other way,” wrote William Stump for the Sun Magazine. The change in elevation was 1,500 feet over six miles of road.

During his last years of teaching at Philip’s Delight one-room school in Frederick County, Md., William McGill’s day began at 7 a.m. when he would get in the station wagon and drive up Catoctin Mountain on roads “so winding and narrow that he blows his horn constantly to warn the lumber wagons which frequently come the other way,” wrote William Stump for the Sun Magazine. The change in elevation was 1,500 feet over six miles of road.

He would stop at the farms and cabins and pick up the older school children and then take them back down the mountain to Thurmont High School. Many of them were his former students so he would catch up with their lives and their studies during the trip.

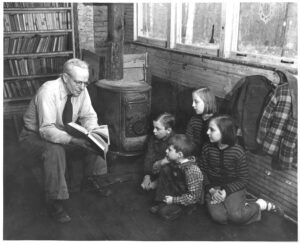

Once he dropped them off, he would turn around and head back up the mountain. If he passed the homes of any of his current students, he would stop to pick them up. When they arrived at Philip’s Delight School, it would already be warm because two students who lived closest to the school had the job each morning to fetch wood from the shed and get the fire started in the iron stove that served as the building’s heating system.

“It was still cold at times because it wasn’t insulated,” said former student Austin Hurley of Thurmont.

Another former student, Betty Willard of Thurmont remembered that on those cold days the students were allowed to move their desks so that they were closer to the stove. Also, because the school did not have electricity when she attended, foggy days would make it hard to see inside the school since the windows were only on one side of the building. On those days, the students were allowed to move their desks closer to the windows in order to be able to read their books.

Like many other buildings on the mountain, Philip’s Delight School had no indoor plumbing. The students had to use the two outhouses behind the school.

“You just had to watch out for snakes, bees and spiders when you opened the door,” Betty Willard said.

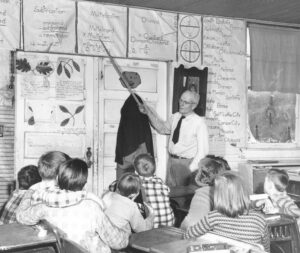

Inside the school, the wooden floor of the school was black from the oil it was polished with to keep down the dust. Seven rows of desks filled the room and bookshelves, coat racks and blackboards were mounted on the walls. The walls were in need of a fresh coat of paint, but it was hard to tell this because posters covered just about all of the free space on the walls.

The posters were part of McGill’s teaching style. He told The News, “If a fifth grader has forgotten something basic from the previous year all he has to do is look around. In fact, there’s hardly a spot to rest a day-dreaming eye without absorbing knowledge.”

Most of the students arrived by 8:30 a.m. The girls would often bring flowers to put in bottles to brighten the room. The boys would get buckets and walk down a lumber trail to the Willard Farm a quarter mile away. They would fill the buckets with water and then walk back to the school. The water they brought would be the school’s water supply for the day.

The students each brought their own tin cup to school. If they got thirsty during the day, they would use a dipper to get water from a bucket and fill their cup.

The school had electricity, but only after January 1952. Up until that time, a student would ring a school bell to note the beginning of classes. After that time, an electric buzzer was used.

The school day started each morning with the students reciting The Lord’s Prayer and the Pledge of Allegiance.

Then McGill would begin teaching his lessons to seven different grades of students with the skill of a master juggler. Stump described one scene this way:

“Seating the first-graders with picture books, he sends third, fourth and fifth graders to the blackboards with instructions to write the names of the characters in their books. Looking at his watch, he reads aloud with the seventh.

“McGill is not still for a second. Neither is he excited—although every second is one of enthusiasm for him,” Stump wrote.

At lunch time, many students walked home for lunch, but others ate at the school. Though some of the schools in Frederick got a hot lunch program earlier, hot lunches didn’t come to many of the county’s rural schools until 1923 and even then, calling it a “hot lunch” was generous.

“At Philip’s Delight hot cocoa is served at noon each day and the milk for this beverage is carried by the teacher for a distance of about six miles to the school. There are about 30 children enrolled in the school,” The News reported.

Some other rural schools would have hot soup instead of cocoa. The purpose wasn’t for the cocoa or soup to be lunch but to supplement the lunch the students brought from home.

Before the students could eat their lunches, they would say grace. Then McGill would sit with them and talk while they ate.

After lunch, the student would play outside while McGill sat on the porch watching over them. Once recess had ended, there would be another session of afternoon classes until the day ended and McGill became a bus driver again.

Betty Willard remembered that McGill would also take the students on field trips. She remembered one such trip when McGill had all of the students bring a sack to take a field trip to gather mushrooms. However, as they walked through the woods to the mushrooms, McGill would have students identify trees and wildflowers that he pointed out.

McGill said of his teaching philosophy in The News, “I’m strong on fundamentals; you won’t believe it, but I talked to a high-school student not long ago who said the capital of the United States was Annapolis. That why I stress places and locations so much; I’ve always done it and I always will.

“Yet it’s more than that. I teach the fundamentals of religion—because there are no churches up here,” McGill said in the Sun Magazine.

He put the school’s location to his benefit in teaching, taking the students on walks in the woods to view animals or using acorns for counting. His goal was to keep them busy and to have fun and rarely did he have discipline problems.

“And in a school like this, every last pupil gets close attention from the teacher—and the young ones benefit from being in the same room with the older ones,” he told The News.

Betty Willard enjoyed working with the younger students when she finished with her own lessons.

“I think that is where I got the desire to teach,” Willard said. She taught school for 40 years, including teaching at the last two-room school in the county, which was in Foxville.

Closing the school

Closing the school

When McGill was transferred to Catoctin Furnace School in the middle of the 1954-1955 school year, no other teacher could be found to take his place at Philip’s Delight and so the decision was made to close the school. With only 13 students in the school, Superintendent Eugene Pruitt decided that two-thirds of the costs to operate the school could be saved by bussing the students to Catoctin Furnace School, and as an added benefit, McGill would still be teaching them.

McGill retired from teaching in 1958 at the mandatory age of 70.

“I’ve tried to give an education and make it pleasant for the pupils. I know I’ve had a good time,” McGill told the Frederick Post.

When this teacher of the county’s smallest schools died at age 85 in 1973, it made the front page in The News.

According to former student, Gideon Willard of Thurmont, the school building sat deserted until 1961. After a snowstorm, the old roof was overburdened with snow and collapsed and the school had to be torn down.

Though Philip’s Delight was one of the last one-room schools in Maryland, the last one-room school to close down was in Tylerton, a small island community in the Chesapeake Bay. When it closed in 1994, it had only nine students with five of them moving on to middle school the next year.

You might also enjoy these posts:

- “Gentleman of the Old School”: William McGill & Frederick County’s Last One-Room School (Part 1)

- LOOKING BACK 1959: Train crashes into Garrett County school bus killing seven children

- Small-town high school students prepare for the journey of a lifetime in the middle of the Great Depression (Part 4)