On Christmas Day 1924, the American Cellulose and Chemical Manufacturing Company gave the world a gift that continues to this day. It came with little fanfare, probably because the plant had seen so many delays in opening that “It seemed the gods themselves had declared war on the Cumberland plant,” Harry Stegmaier, Jr. wrote in Allegany County–History.

On Christmas Day 1924, the American Cellulose and Chemical Manufacturing Company gave the world a gift that continues to this day. It came with little fanfare, probably because the plant had seen so many delays in opening that “It seemed the gods themselves had declared war on the Cumberland plant,” Harry Stegmaier, Jr. wrote in Allegany County–History.

However, the Dreyfus Brothers had pushed forward, mounting roadblock after roadblock, to create an artificial silk from cellulose acetate fiber that would be free from the drawbacks of silk.

Drs. Camille and Henri Dreyfus began pursuing their dream in the early 1900s as they conducted chemical experiments in a shed in their father’s garden in Switzerland. By 1910, the brothers had developed cellulose acetate lacquers and plastic film.

This success led to a commercial product that allowed the brothers to fund further experiments. They built a manufacturing plant and made a nonflammable motion picture film base that eventually replaced the volatile cellulose nitrate base, according to the Celanese Corporation website.

The Dreyfus brothers continued experimenting and by 1913 they had created a high-quality acetate fiber yarn.

World War I took their research in a new direction, and they produced a flame-resistant acetate lacquer coat (called acetate dope) for fabric used to cover airplane wings and fuselages. The brothers also moved their operations to Britain from Switzerland where they believed they would be safer. The new company was called the British Cellulose and Chemical Manufacturing Company, Ltd.

With the U.S. entrance into WWI, negotiations began to bring the British Cellulose and Chemical Manufacturing Company to America. The potential location for an American plant required that it be away from the coast to avoid possible Zeppelin attacks, near a plentiful source of water, and near the cotton belt, since cotton was the primary cellulose source the company used.

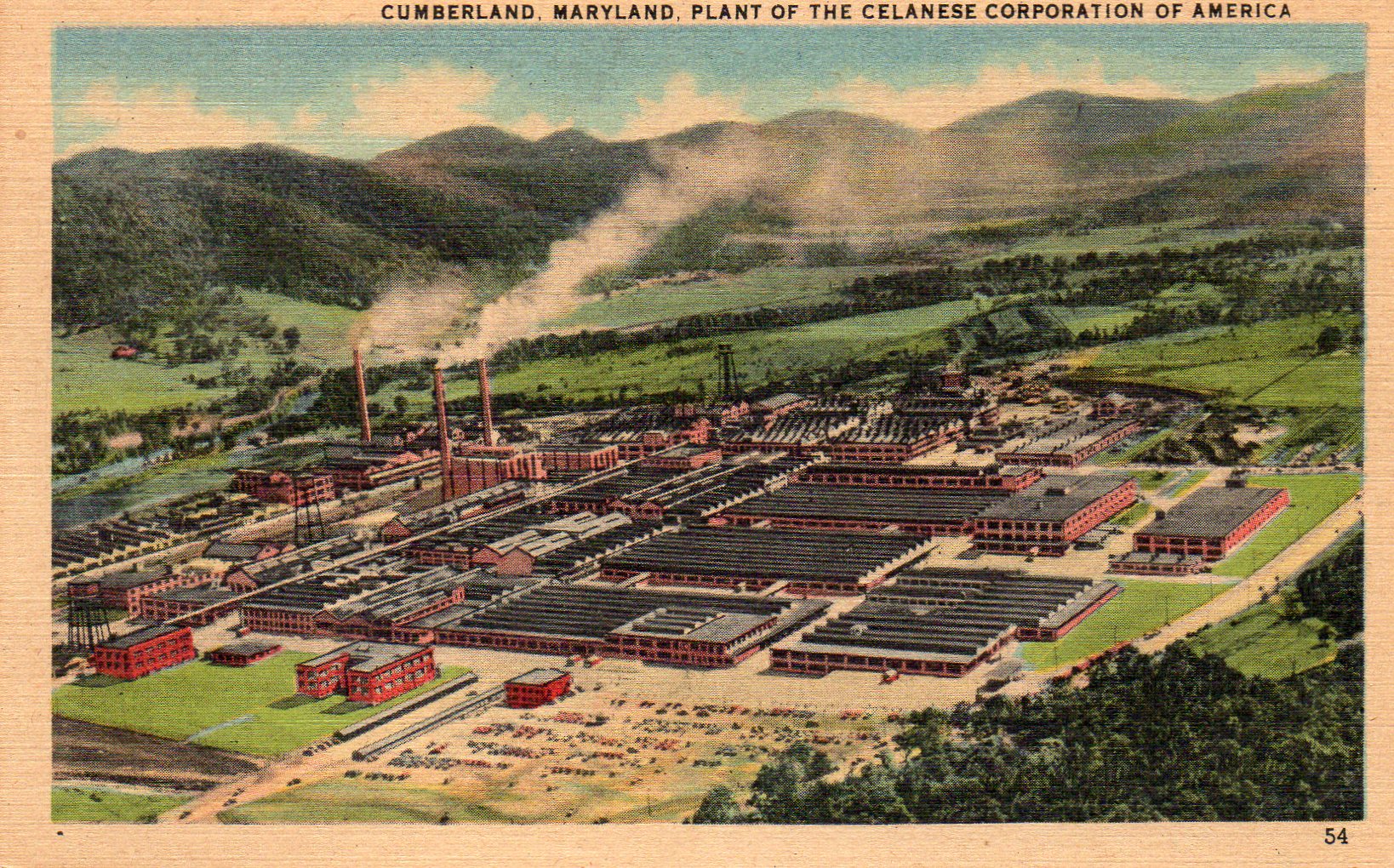

“Cumberland’s location suited the company’s requirements. Moreover, it possessed good rail transportation and lay near a source of cheap fuel,” Stegmaier wrote.

The Cumberland Development Company bought three farms and parts of three others to create the plant site.

“In 1918, after a year of negotiations and delays, Cellulose & Chemical Manufacturing Company, Ltd. was opened in Cumberland, Maryland, to produce acetate dope for the U.S. military,” according to the Celanese Corporation website.

Before plant construction could be completed, though, the war ended, and the demand for the acetate lacquer nearly disappeared. Work continued on the plant, but at a snail’s pace because of construction and labor issues.

Meanwhile, operations in the England plant resumed, and in 1921, the Dreyfus brothers produced the first cellulose acetate yarn. Not only did it not have the problems silk had, it was far less expensive. Cellulose acetate yarn sold for $9 a pound as opposed to $20 a pound for silk.

Cellulose acetate yarn had its own production problems that needed to be worked out. The initial yarns couldn’t be manufactured with a consistent diameter. The biggest problem was the textile industry didn’t know how to use the yarn, in part, because the traditional dying process to create fabric colors didn’t work on cellulose acetate yarn. The company set to work developing new machinery, processes, and dyes to address the problems.

This early form of artificial silk was used from primarily for crocheting, trimming, and effect threads, and for popularly priced linings, according to the Celanese website.

In 1922, when the company decided to trademark its new product in England, it offered a 5-pound prize for a name. Celanese, which was said to be a combination of “cellulose” and “ease”, won.

By 1923, the company had $13 million dollars in orders. Then a textile depression hit, and all the orders were cancelled, which threw the company into financial problems.

Work on the Cumberland plant continued with portions opening, but then the spring of 1924 saw two floods devastate the region. The spinning and textile buildings at the plant were damaged. Materials washed away in the flood waters and machinery was covered in mud.

This caused increased financial difficulties for the company, and Cumberland officials began worrying the deal would fall apart and the company wouldn’t open its Cumberland plant.

The race to start production started and on Christmas day, the company began weaving a refined cellulose acetate yarn that addressed many of its problems. While the event revolutionized the textile industry and saved the company, it only merited a small article on the Cumberland Evening Times business page, which noted “It is said that the demand for the silk is far greater than the supply and that the market for it will be widespread.”

This new yarn was an instant hit, so much so, that the silk industry tried its best to discourage companies from using it. Users realized the celanese had good wrinkle recovery, good draping, and was quick drying. It had multiple retail uses in things like rugs, bathing suits, and clothing. The only problem was that other companies didn’t have the machinery needed to weave the new yarn. To continue the growth of the product, the company started weaving the yarns into fabrics in 1926.

“The remarkable rise in the use of Celanese yarns by the mills in this country has been responsible for one of the most interesting chapters in fabric development that has been noted in the textile markets since the development of synthetic fibers,” the trade journal Textile Bulletin reported.

The Cumberland plant, which had 550 employees in 1924, soon grew to have 7,000 employees in Cumberland 10 years later. During World War II, demand for Celanese skyrocketed because it was used in parachutes.

The success of Celanese was so great that in 1927, the American Cellulose and Chemical Manufacturing Company became the Celanese Corporation.

Celanese continued to win over customers. According to the Celanese website, “At the time acetate was introduced in the U.S. practically all better dresses were made of silk; by the 1950’s less than two percent were silk.” The Celanese was one of the dominant sellers in the market at the time.

As new synthetic fibers and competitors entered the market, Celanese began looking to diversify its product offerings. This initially helped the company’s sales grow, but by the late 1960s, many of its operations for these new products were sold off when foreign markets slowed.

As the company grew and expanded into other countries and states, operations began shifting. By the time the Cumberland plant closed in 1983, only 310 employees remained. The plant was eventually razed and the state prison built on the former site.

The Celanese Corporation still exists today, although not in Cumberland. It is based in Texas with a number of foreign offices and employs around 7,500 people. The company has also diversified its offering in various areas, including engineered materials, acetate tow, chemistry, food ingredients, and polymers.