Some historians call the War of 1812 the second American Revolution. Less than a generation after America won her independence, she once again found herself battling Great Britain. It was a war that neither side wanted because both countries were still trying to recover from the original American Revolution.

Some historians call the War of 1812 the second American Revolution. Less than a generation after America won her independence, she once again found herself battling Great Britain. It was a war that neither side wanted because both countries were still trying to recover from the original American Revolution.

The British fought a defensive war in the early years of the War of 1812 because they were also fighting against Napoleon Bonaparte and the French army and navy in Europe. By 1814, Napoleon had been defeated and the British turned their attention more fully to ending the war with the United States with a victory. Up to this point, most of the fighting had been around the Canadian and U.S. border to the north. In the Mid-Atlantic, the British had started a blockade in 1813.

Preparing for War

In July 1814, President James Madison called on the states to supply militia to defend the young country. According to William Lowdermilk in A History of Cumberland, Maryland, “Maryland was required to furnish one Major-General, three Brigadier Generals; one Deputy Quartermaster-General, one Assistant Adjutant-General, and six regiments, to consist of 600 artillerists, and 5,400 infantry.”

However, war is a political question as well as a military one, and Maryland was split on the need to go to war. The Federalists called themselves the “Friends of Peace.” Their position was that the U.S. should fight only to defend its borders and not seek to take territory from Canada, which had been happening on the northern front of the war. The Democrats were called “War Hawks” and fully supported not only a defensive war but an offensive one.

In the fall elections of 1814, the Democrats nominated Thomas Cresap, Thomas Greenwell, Benjamin Tomlinson and Upton Bruce to the state legislature. It was the Federalists who swept the election, though. Jesse Tomlinson, William McMahon, William Hilleary and Jacob Lantz were elected and sent to Annapolis to represent the county.

Around that time, the county also moved towards filling its portion of the state’s militia quota and there was “a considerable degree of enthusiasm manifested,” according to Lowdermilk.

While county residents hadn’t been engaged in any military conflicts since the Revolutionary War, volunteer groups had been meeting to drill, shoot targets and discuss fighting techniques. Lowdermilk wrote that some of the volunteers had served in the Revolutionary War as members of the Maryland Line.

Maryland soldiers had distinguished themselves for their bravery and ability during the Revolutionary War. They were so dependable that it is said George Washington called the Maryland regiments his “Old Line,” which is where one of Maryland’s nicknames as “The Old Line State” comes from, according to the Maryland Archives.

Answering the Call

In the fall of 1814, two companies were formed in Allegany County that totaled 227 fighting men. Captain Thomas Blair formed one company primarily with men from Cumberland. Captain William McLaughlin formed his company with men outside of the city.

Lowdermilk noted of Blair’s company, “The Company formed in Cumberland was made up of excellent material, the organization having been effected some months before.”

Once formed, the men marched to Baltimore in August where they became part of the First Regiment of Maryland Militia, under General Samuel Smith and Colonel John Ragan. They spend most of their time at Camp Diehl wondering if they would see any fighting.

Seeing Action

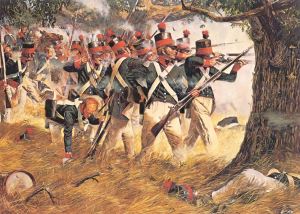

On September 12, a British fleet of more than 30 warships and transports sailed up the Chesapeake Bay and landed 5,000 troops on the North Point peninsula. The American militia of 3,000 men, including the soldiers from Allegany County, met the British troops at Godly Wood, eight miles north of the British landing point.

The two sides exchanged musket and artillery fire for about an hour before the British troops’ superior size forced the Americans back toward Baltimore. However, the Americans inflicted heavy casualties on the British, including mortally wounding the British commander Maj. General Robert Ross.

With the loss of the lionized Major-General Robert Ross to tree-hidden American sharpshooters, the British advance toward the city slowed whilst the powerful fleet lay useless against Fort McHenry because of the tremendous amount of blockage which had been dropped into the channel,” according to the General Society of the War of 1812 web site.

The bombardment of Fort McHenry, which led to Francis Scott Key to write the words to “The Star-Spangled Banner,” began the following day.

Celebrating

Back in Allegany County, news reached the residents of the American victory on Lake Champlain between New York, Vermont and Quebec and the people celebrated. “Processions paraded the streets, singing and shouting, and the entire population took part in the celebration,” Lowdermilk wrote.

The county’s soldiers were mustered out on October 13, after which they returned to the county and were disbanded in early November.